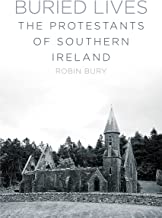

Buried Lives: the Protestants of Southern Ireland

Buried Lives: the Protestants of Southern Ireland

Robin Bury, The History Press Ireland, Dublin 2019. 20.00

ISBN: 978-1-84588-880-0

Robin Bury, a member of the Church of Ireland, who grew up in East County Cork in the 1950s and 60s, has examined the long and troublesome experience of the Protestants in what he calls ‘Southern Ireland’. He uses this term rather than the ‘Irish Free State’, or the ‘Republic of Ireland’ as he covers the period from before the foundation of the independent Irish state until the present day.

What was it that turned the once strong and thriving southern Irish Protestant community into an ‘isolated, pacified community’ living an isolated parallel existence from mainstream society? How did the section of Irish society that produced some of the nation’s greatest writers; Jonathan Swift, Oliver Goldsmith, Oscar Wilde, WB Yeats, J M Synge, George Bernard Shaw, and Samuel Beckett; international brands like Guinness, Jacob’s Biscuits and Jameson whiskey decline from 10% of the population in 1911 to less than 3% in 2011? What happened? Was this decline natural, or was it helped by human intervention in some way?

The decline began to accelerate in the period 1919 – 1923. Bury examines carefully the statistics from this period in his first chapter taking into account the number of people directly or indirectly connected with the Royal Irish Constabulary and the British armed forces, those who died in the Great War and the postwar Spanish flu epidemic and natural decrease. Excluding the approximately 64,600 people included in these categories, Bury estimates that 41,856 southern Irish Protestants left the country; whether by direct intimidation, or their own apprehension and fears of being trapped in what was quickly becoming a conservative, Catholic, Anglophobic state.

The newly formed Irish Free State certainly had no policy of driving the Protestants out. This was certainly not the case with the IRA ‘irregulars’ who – in east Cork at least – targeted a large number of Protestants; small farmers, businessmen, shopkeepers and one Church of Ireland clergyman. They were seen as the enemy; ‘land-grabbers’, ‘landlords’, ‘Freemasons’, ‘Orangemen’, ‘Imperialists’, ‘informers’; all to justify their killing.

Things got so bad, that the Archbishop of Dublin and two other leading southern Protestants had a meeting with the Free State leader, Michael Collins after thirteen Protestants were murdered in the Bandon valley. They wanted to know if the Protestant minority should stay on in the county. Collins assured them that, “the government would maintain civil and religious liberty”. However, Collins wasn’t in much of a position to do much to help. IRA irregulars assassinated him a few months later.

This is a period that many people, especially in today’s modern Ireland would wish to bury; hence the title, Buried Lives. The author is meticulous in his documentation of this tragic, overlooked, and often deliberately ignored aspect of Irish history. The second chapter records some survivors’ harrowing stories; many given as evidence to the Southern Irish Loyalists Relief Association and the Irish Grants Committee to try to win some compensation for their loss. These personal stories show the genuine terror these survivors experienced.

Bury shows how southern Protestants adapted to life in DeValera’s Free State by living quiet, but largely separate lives, rarely socialising outside their own communities; they ‘kept their heads down’ and got on with things in a virtual parallel universe. Until recent times, the mainstream Irish attitude in the South was deference towards the Catholic Church and a romantic rural nationalism. The Protestants survived because they became an insignificant minority.

Bury also looks at the influence of the infamous Ne Temere decree issued by Pope Pius X in 1907. Before 1926, only 6.1% of Protestant brides were marrying Catholic men; by 1971 the figure was 30%. Today, it’s closer to 50%. Children of couples married since Ne Temere are brought up in the Catholic faith, further contributing to the decline of the Protestant communities in the State.

Bury looks at the notorious Fethard-on-Sea boycott of 1957 where all Protestant-owned businesses, farms and even individuals were boycotted after the marriage of a local couple broke down and the Protestant wife, Sheila Cloney, took her children away from the Co Wexford town. The boycott was organised by the local parish priest, Fr William Stafford and lasted for nine months.

Happily, the Southern State has changed a lot in the last sixty-odd years since the Fethard-on-Sea boycott. This is not due to the silent minority – the marginalised Protestants – but people, mainly women, brought up in conservative, Catholic Ireland – who said, we’re not going to put up with this anymore. Strict censorship has gone; Article 44 of the constitution, which gave a special place in society to the Catholic Church, was removed, divorce and contraception were legalised, homosexuality was decriminalised. There is still a long way to go, people are still assumed to be at least culturally Catholic, but perhaps the Southern Protestants may yet find a place in the sun. The rise of Sinn Féin electorally in the Republic may stymie this; it may not. Time will tell.

This book is a useful introduction to a difficult and painful period in Irish history. It has an appendix on the victims of the Bandon valley massacres and extensive notes and a bibliography for further research for any reader wishing to examine the author’s case in detail.

Reviewed by David Kerr

spiritofthedrum said

Thanks for this David – an interesting book. (I wonder if others have noticed the author’s name and its relation to the title? 😉 )

LikeLike